Pete Jorgensen

Plant Science & Horticulture

Grassroots Community Food Growing Projects for Personal and Cultural Reorientation

The extent of humankind’s destructive impact on planet earth is of such a magnitude that some claim we have caused a new geological era - ‘the Anthropocene’ (Steffen et al., 2007; Lewis & Maslin, 2015). Others believe ‘the Capitalocene’ more accurately identifies the cause (Moore, 2017). Contemporary capitalism, underpinned by an unsustainable culture of consumption and an irrational ideology of endless economic growth, does appear to be the main driver of environmental destruction and social fragmentation (Piketty, 2014). As part of this system, globalized corporate agriculture and the commodification of food contribute significantly to many social and environmental ills through land dispossession, social and economic insecurity, habitat loss, unsustainable resource use, toxic pollution from agrochemicals, and greenhouse gas emissions (Bonanno & Wolf, 2018a; Kimbrell, 2002; Smith et al., 2016; Paerl & Scott, 2010). If we are to lessen the risk of making planet earth uninhabitable for human beings and reduce the suffering of the non-human world, moving beyond an unsustainable socio-economic system driven by consumer capitalism is imperative (Ivanova et al., 2016; Dietz & O'Neill, 2013).

Grassroots community food growing projects (GCFGPs) may provide a useful space within which a radically different culture can be imagined and practised. Food is a ubiquitous human requirement and interaction with plants can reinvigorate social relations and inspire and instil reverence for the natural world (Lumber et al., 2018; Pretty, 2002). This review will explore whether involvement in GCFGPs can cultivate relationships between people, place, and the natural environment, that transcend material instrumentalism. In short, whether a practise of community can usurp the dominance of commodity. While I recognize the planetary nature of the issue, my focus will be on western capitalist societies as they have shaped, and continue to drive, globalized consumer capitalism. They also have significantly higher per capita ecological footprints than most other regions (Amin, 2009).

For clarity, the term GCFGPs is intended to include any project that involves the growing of food in a communal way or for a communal purpose (friends, volunteers, neighbours, community groups, community supported agriculture etc.) that has emerged from a bottom-up rather than top-down organizational approach. I will begin with a brief genealogy of neoliberalism, outlining how its progenitors worked to disenfranchise true democracy, creating a powerful capital-driven hegemony. Next, I discuss how GCFGPs could provide opportunities for the exploration of self-transcendent goals counter to the normative pressures of neoliberal subjectivity, highlighting the potential for goal reorientation to enable the formation of new identities. Following this, I contemplate group identity and community, providing examples that reveal tensions and incongruities within GCFGPs when examined in a counter- hegemonic context. In the penultimate section, I will discuss how the provision of a strong cultural framework could enable the embodiment of new values and identities through physical and social activity. To conclude, I will briefly summarize my findings and propose research that could explore the topic further.

The Neoliberal Paradigm

Neoliberalism currently dominates contemporary socio-economic structures and is implicated in the conditioning of relationships and the construction of identity (Greenhouse, 2010; Chandler & Reid, 2016). Neither a robust discussion nor a fully nuanced evaluation of neoliberalism is within the scope of this review. Besides, it remains a contentious topic provoking much debate, disagreement, and contradiction (Birch, 2017; Fine & Saad-Filho, 2017). However, an emerging body of literature provides crucial insight into its genealogy and core tenets, and it is important to explore these to fully comprehend the wider context within which GCFGPs are situated.

Neoliberalism was gestated as a philosophical ideology by a group of Austrian economic thinkers during the troubled 1930s; Von Mises, a former adviser to the short-lived imperial fascist dictator, Engelbert Dollfuss, was a prominent figure in its establishment (Slobodian, 2018). This movement solidified with the formation of the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947 by a variety of actors including Von Mises, Frederick Hayek (a student of Von Mises), Karl Popper, an Austrian philosopher, and US-born economists Milton Friedman and George Stigler (Mirowski & Plehwe, 2009). Their project was based on the reinvention of classical liberalism (hence the ‘neo’ and the occasional synonymity with neoclassicism). Common themes throughout the various flavours of neoliberalism include: opposition to collectivism; espousal of the free market; and, similar to postmodernism, a denial of metanarratives (Gilbert, 2014; Slobodian, 2018). Neoliberal schools of thought began to have significant political and economic impact in the 1970s when the most obvious vector of its success - financialization – was brought to the fore (Epstein, 2005). It is often believed that the bedrock of neoliberalism is the roll-back of the state which also began in the 1970s, but this is only partially true. The state has been an essential tool in its establishment, creating and reinforcing the legal frameworks within which markets operate. These include: transnational trade agreements and legal restraints on the collective action of the workforce; selling property and services owned collectively and managed by the state to private capital interests; provision of public money for research and development, subsidies, and rescue packages when markets fail; the use of state authorities to violently suppress opposition (Perkins, 2004; Slobodian, 2018; Mirowski & Plehwe, 2009). Veiled behind the mantra of deregulation and the free market, there has been continual consolidation of businesses into larger, more powerful organizations (Piketty, 2014). The result is the evisceration of true competition at the macro-scale while stimulating more fierce forms of competitiveness among those from whom capital is being harvested (Birch, 2017). Notably, this inversion of competition serves to disempower the population and block the emergence of collectivism, save for the undemocratic collectives of the monied classes – think tanks, industrial lobby groups, and financial and business organizations (Harvey, 2007; Gilbert, 2014). Under neoliberalism, you can choose any lifestyle you want, so long as it's a neoliberal one.

The neoliberal movement was keen to avoid affiliation with any one political party or movement, instead seeking to infiltrate all of them to achieve unopposable influence in the mechanisms of the state (Slobodian, 2018). Their project was highly successful, accelerating during the 1980s when the governments of the UK and USA sought to propagate neoliberal ideology using all means available. Carefully engineered, centrally- planned, and state-implemented socio-economic plans were used to transform hearts and minds creating a fragmented, individualistic population (McGuigan, 2014). Meanwhile, the deregulation of private finance capital was used to facilitate widening inequality and the accumulation of ever-increasing amounts of wealth in a few hands (Piketty, 2014). This wealth imbalance translated easily into a hegemonic power structure dominating markets and the media, and governing decisions and conduct in every area of life, in almost every area of the world (Fine & Saad-Filho, 2017; McChesney, 2001; Gilbert, 2014). Direct political funding and well-financed lobbying were used to steer politics, leaving populations disenfranchised and apathetic (Ayers & Saad-Filho, 2015). For neoliberals true democracy is undesirable – truly free elections could result in politically established collectivism. In countries where this does occur, other tools are deployed to destabilize and remove elected governments from power. Military coups, severe economic sanctions, and psychological operations, including propaganda proliferated through popular media, have been profoundly evident, perhaps most notably in South America (Sierra Caballero, 2018; Perkins, 2004; Harvey, 2007).

It's important to acknowledge that neoliberalism is not wholly novel, it emerged from a process of capitalist advancement that dates back centuries, if not millennia (Neal & Williamson, 2014; Moore, 2017; Moore, 2018; Fine & Saad-Filho, 2017). What is different is how this paradigm was deliberately and systematically entrenched into our physical, economic, social, and psychological infrastructure on such a massive scale. Older forms of capitalist hegemony often required more overtly violent methods of coercion, but the contemporary form has created a self-perpetuating culture of social control and self- discipline. The commodification of the self, hyper-consumerism, gross inequity, and systematic environmental degradation have been normalized and even valorized (Piketty, 2014; Dilts, 2011). Hopefully, this short synopsis of the neoliberal project will have emphasized the breadth and depth of its reach and the importance of how it controls the structures upon which we hang both our culture and our personhood. Next, I will examine how the neoliberal paradigm influences individual subjectivity. Understanding this is paramount if we are to truly evaluate the capacity of GCFGPs for providing space and nourishment for a personal and cultural transition to a more sustainable future.

The Neoliberal Self

In the neoliberalized society, social Darwinism expressed through the overarching norms of competitive individualism and self-reliance has become so encapsulating it is almost invisible (Antonio, 2007; Gilbert, 2014). This gives rise to the neoliberal-self (NS) (McGuigan, 2014). Based largely on Foucault’s ideas of governmentality, the NS internalizes neoliberal modes of conduct which require obedience to market demands for a precarious and mobile workforce (Hamann, 2009; Read, 2010). Use of language, even in mundane discourse, is framed within economic terms and concepts, for example, the NS ‘invests’ in their human ‘capital’ through education and training with the aim of becoming more marketable and outcompeting others (Chun, 2016; Shin & Park, 2016). The financial rewards for conducting oneself in accordance with the demands of neoliberal capitalism are real, usually allowing for individuals to meet their basic needs and often enabling a historically high level of material affluence. Conversely, punishment for failing to successfully compete as a neoliberal human resource is severe; at the extreme - pariah status, poor mental and physical health, homelessness, and starvation (Elliot, 2013). Punishments apply regardless of reason – misfortune, unfair play, poor health, or conscious refusal to participate – and are considered a fault in the individual, not society (Hamann, 2009).

Neoliberal capitalism may portray itself as a means for achieving individual liberation, but for most “individualization is a matter of institutionalized obligation, not free choice.” (McGuigan, 2014: 233-234). To consider whether GCFGPs are spaces where this internalized state can be explored and challenged I will first look at how they may influence goal-orientation.

Goals and Identity

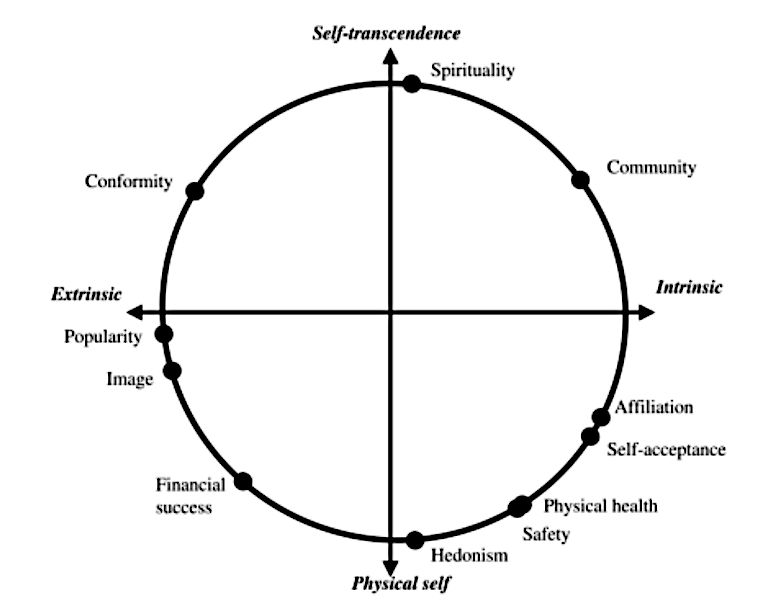

Constrained by neoliberal socio-economic power structures, the NS seeks to realize freedom, self-efficacy, and individuality via purchasing decisions – cars, music, toiletries, clothing, tourism, food, electronics, and so on (McGuigan, 2014). This commodification of self-expression is how everyday neoliberal norms drive materialism (the prioritization of wealth and status-oriented goals), disassociating people from their community and environment, and fuelling economic activities that are the cause of so much serious environmental degradation (Kasser, 2016). A conceptual map of goal domains developed by Grouzet et al. (2005) can help illustrate how GCFGPs might counter this behavioural chain (figure 1). The map is formed from a circumplex divided into four key domains formed from two oppositional pairs of goal orientation - ‘intrinsic’ versus ‘extrinsic’ and ‘physical self’ versus ‘self-transcendence’ Stimulating goals that lie in the ‘extrinsic’ / ‘physical self’ region results in consumptive behaviour, whereas activating goals in the opposite region – ‘intrinsic’ / ‘self-transcendence’ results in pro-social and pro-environmental behaviours (Crompton & Kasser, 2009).

A circumplex map of goals and associated goal-orientation (Grouzet et al., 2005).

Smith & Stirling (2018) suggest that GCFGPs may provide the opportunity to experience real physical environments and activities that stimulate intrinsic self-transcendent goals and enable the agency of participants in ways they may not experience elsewhere. There is evidence to support this. Dobernig & Stagl (2015) report that motivating factors for urban community gardeners in New York included contributing to food security for the planet and cultivating food in an environmentally friendly way. A long-term member of a community farm in East Sussex, England, expressed explicit desire for spirituality / self-transcendence, “I want to work toward a deeper and more holistic way of seeing.” (Ravenscroft et al., 2013: 634, emphasis added). Following involvement in a CSA in Hungary, Kis (2014: 290) says, “ … what captured me was the spirituality of this whole thing…a useful and meaningful devotion to people … ” (emphasis added).

It appears that GCFGPs are places where people can explore goals that are more eco-social in nature - for some this may form an important aspect of challenging the NS. However, goal orientation can be volatile and easily influenced by external prompts, particularly through universally pervasive advertising (Lindenberg & Steg, 2014). Crompton & Kasser (2009) suggest that enabling people to create ecologically- oriented identities may provide more resilience to normative external cues. A longitudinal study of community gardeners in New York indicates that pursuing self-transcendent goals can help build resilient self-transcendent identities (Sonti & Svendsen, 2018). Coded analysis of interviews revealed a strong theme of non-instrumental values being expressed, such as love for nature, the planet, and other people. One participant identified themselves as ‘a nature girl’ (Ibid.: 1195). Another said, ‘I don’t go to church to get in touch with god, I sit under a tree’ (Ibid.: 1198). Here we may see the emergence of what Clayton & Opotow (2003) call the ‘environmental identity’ - a construct that embraces multiple meanings emerging from our relationship with the non-human natural world, solidified though social interaction.

Group Identity, Community and Counter-Hegemony

The social aspect of GCFGPs is expressed through community building and is a strong motivational factor for involvement in GCFGPs (Spilková & Rypáčková, 2019; Ravenscroft et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2017; Sonti & Svendsen, 2018). It is important to understand the biological basis for this desire because it can help inform analysis of the motivation to join GCFGPs and why tensions may arise within them. Belonging to groups, or tribes, is a fundamental humanPage 8 of 19 need stemming from our drive for survival and reproduction – natural selection favoured cooperative individuals (Boyd & Richerson, 2009; Raafat et al., 2009). The sense of self that people derive from these affiliations is so influential that they may make choices that seem objectively irrational (Tajfel et al., 1971; Levine et al., 2005). Intergroup differences and intragroup similarities are exaggerated, facilitating clarity in making quick judgements about who is like (trustworthy), and who is unlike (suspect), resulting in a depersonalized mode of interrelation where individual characteristics are secondary to those held by the group (Hogg & Reid, 2006); recent evidence suggests that these prejudicial cognitive processes are hard-wired into the brain (Hein et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2017).

Marginalized outgroups are thematic of neoliberal society where misfortune is often individualized and portrayed as the consequence of bad choices, whereas the environmental and social context is ignored (Adams et al., 2019). This encourages the perception of the vulnerable and disadvantaged as lazy, stupid, or burdensome – a group resented by those who see themselves as successful neoliberal citizens; individuals then internalize and identify with their situation reinforcing the ingroup / outgroup social dynamic (Hughes, 2015; Dej, 2016). Involvement in GCFGPs has been found to help stigmatized people, such as the unemployed and the homeless, to improve their self-image by enabling them to make productive contributions to their community (Flachs, 2010). This may be beneficial for individuals and help dissolve barriers on a local level (Crossan et al., 2016), but it does not seem to directly challenge the power structures that give rise to stigmatization in the first place. Indeed, the role GCFGPs play in addressing the deeper roots of socio-economic issues has been the subject of much debate and disagreement. Some commentators highlight the inherent failure of many GCFGPs to confront these issues and suggest that they may even unintentionally support neoliberal policies – something I will expand upon later in this review.

Similar tensions are implicit in Ravenscroft et al.’s (2013) analysis of community farming in England. Participants were found to be actively experimenting with their identity by bondingPage 9 of 19 with others in the organization as well as the place itself. However, these experiments were often short-lived; many members left the group or no longer actively participated frequently blaming the pressures of work or other outside commitments. This may in part be due to the processive nature of communal identity (Melucci, 1995), but examining interview extracts suggests that the demands of providing unpaid labour were influential. One volunteer reported their shock in receiving “a phone call suggesting certain individuals were not pulling their weight.” (Ravenscroft et al., 2013: 636). A bleak recollection by a paid CSA farmer revealed that unpaid voluntary work on the farm could be very testing, “It was like a prison camp at harvest…” (Ibid.: 636). Perhaps some individuals came to perceive that the demands and pressures being placed on them were little different to the work demands and power structures of the wider world. Such internal tension would no doubt be exacerbated if CSA farmers were earning their living not only from their effort but also from the free labour of the volunteers, who also had to work elsewhere to sustain themselves. Another causal factor could be the creeping marketization of volunteering which undermines the social purpose, meaning, and intrinsic value of the activity (Dean, 2015).

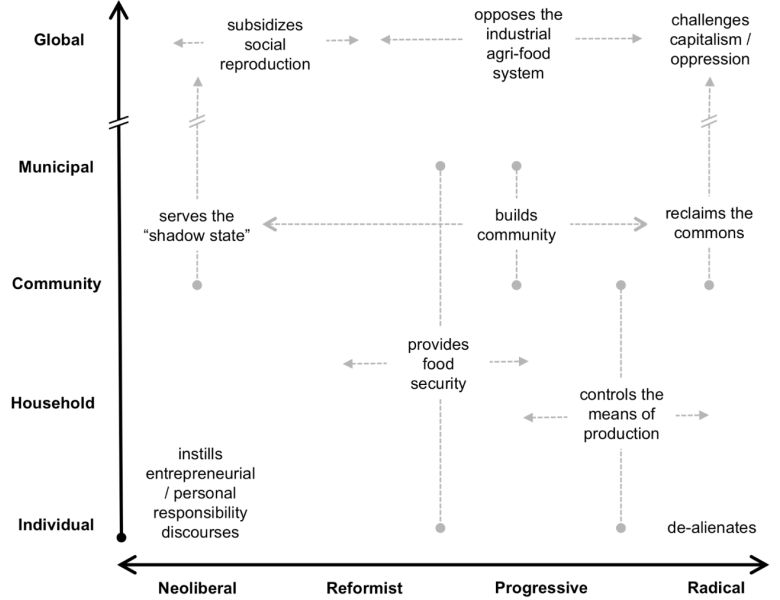

Some qualities of GCFGPs could be viewed as counter-hegemonic, but it is unrealistic to reduce analysis to a dualistic way of thinking; there is much complexity within and between different projects. McClintock (2014) has mapped significant tensions and contradictions between core functions of GCFGPs, positioning them in terms of their affinity with, or opposition to, neoliberal values, and their geosocial scale – see figure 2. For example, GCFGPs have stepped into the space left by the roll-back of state support for people in need by donating to food banks, improving work skills, and providing therapeutic support (Ibid). The intention is to assist those in need, but the indirect effect is to support the neoliberal agenda by reducing pressure on the state and fulfilling the role of the ‘big society’ (McClintock, 2014; Thompson, 2012).

Mapping the social scale of political-economic organisation in urban agriculture in terms of alignment with or opposition to the neoliberal ideology. Dotted lines are intended to indicate factors operating at multiple scales and in heterogenous domains (McClintock, 2014).

Similarly, Bonanno & Wolf (2018b) identify several contradictions evident in food movements that appear counter to the neoliberal regime, but which unintentionally serve to support it. Projects may attract individuals who are seeking a radical change in the power structures of society, yet their activities are often depoliticized and remain in the private, marketized sphere, leaving the absolute dominance of private capital unchallenged (Ibid.). GCFGPs may also act as spaces where individuals who have been disadvantaged, or damaged, by participation in the mainstream economy convalesce and reskill, not as a means of repositioning themselves in radical opposition to it but with the aim of returning to a functioning role in the labour market (Hudson, 2009; Sonnino & Griggs-Trevarthen, 2013). Additionally, many of those working to establish and run such socially valuable projects do so for little or no pay, or without access to secure tenure over land which might be leased from or loaned by wealthy landowners or local authorities (Sonnino & Griggs- Trevarthen, 2013; Ravenscroft, et al., 2013; Milbourne, 2012). Reclaiming private, disused orPage 11 of 19 neglected land as a common space is frequently a motif in the inception of GCFGPs – an action that is easily positioned as counter-hegemonic (Milbourne, 2012; Thompson, 2012; Crossan et al., 2016). However, within the neoliberal regime, publicly owned land is particularly insecure. For example, in the UK over £9 billion worth of public land and property has been sold into private hands since 2014 (Davies, 2019); 135 allotment sites and 72 garden plots were among these sell-offs (Lawson et al., 2019).

Culture

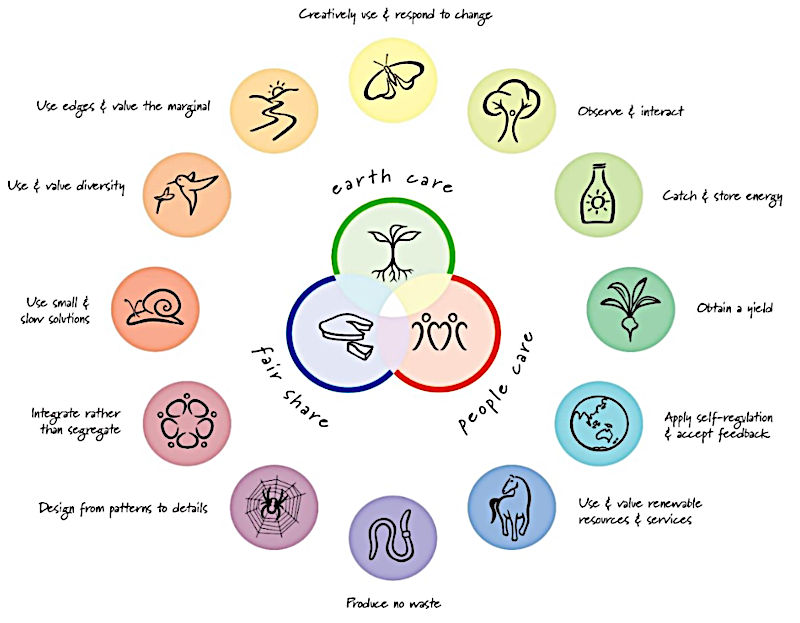

The physicality of engaging in (re)claiming land for community purposes is an example of how values can be embodied through action in the material world and it is through embodiment that new identities, communities, and cultures can be created (Ignatow, 2007). As places of physical and social activity, GCFGPs are ideal zones for enabling relational practises that embody a counter-neoliberal conscience. However, the type and strength of values that come to be embodied may relate to the content and clarity of the stated goals or mission of a project; that is, the language that frames the actions (Lizardo, 2015; Ignatow, 2015). Some GCFGPs appear to lack the characteristics of a well-defined movement; members often feel bound by a loosely defined mutual interests, such as opposition to industrial agriculture or an interest in healthy food (Dobernig & Stagl, 2015; Murtagh, 2010). Others coalesce around more explicit and defined cultural ethics. Permaculture is a good example of this. It can be applied in any sphere of life, but to date, its dominant form is practised as a form of cooperative agroecology, reflecting its etymological origins as a portmanteau of ‘permanent’ and ‘agriculture’. The Permaculture movement has three core values (illustrated in the centre of figure 3) – people care, earth care, and fair share (Pickerill, 2015). All three entail a sense of responsibility and socio-environmental connectedness that is dissonant with the neoliberal pressure to focus on the self. Permaculture also proposes twelve key design principles (see figure 3) of which some, taken out of context, could constitute part of any vacuous corporate mission statement. However, others, such as ‘use small and slow solutions’, are radically different to the capitalist mode of maximizing profit in the shortest time.

‘Slow’ has become an integral expression of resistance and solidarity in diverse contexts, opposing the ever-accelerating treadmill of competitive capitalism by promoting craftmanship, good relations, sustainability, and the quality of everyday experience (Mountz et al., 2015; Pookulangara & Shephard, 2013; Pietrykowski, 2004). The ‘slow food’ (SF) movement gave rise to this trend following its emergence in the mid-1980s when activist Carlo Petrini felt compelled to organize resistance against the spread of fast food culture (Mair et al., 2008). SF has a strong counter-hegemonic ethos that entails taking pleasure from the communal sharing of quality food produced in a socially just and environmentally sound manner (Ibid.). Indeed, embodied social activity combined with pleasure and celebration is a strong theme throughout much of the literature on GCFGPs and appears to be an essential cultural ingredient in the establishment and continuity of many projects and movements (Mair et al., 2008; Sonti & Svendsen, 2018; Cumbers et al., 2018; Crossan et al., 2016; Sumner et al., 2010).

Figure 3: The three core values and twelve design principles of permaculture. Source: https://permacultureprinciples.com, Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0).

Summary

I began this review by identifying links between contemporary capitalism and serious social and environmental issues. The urgent need for the creation of a new culture was highlighted and GCFGPs suggested as places in which a new mode of being might be explored. Counter-hegemonic potential was examined through the lens of goals, identity, community and culturally embodied values. No doubt, my subjectivity is revealed through my choice of topic, but it is not my intention to recommend that GCFGPs should oppose neoliberalism. Some values associated with GCFGPs, such as autonomy, self-efficacy, and productive activity are quite compatible with neoliberal thought, highlighting the complexity of juxtaposing GCFGPs both with neoliberal thought and its sometimes-incongruent reality. Nor should GCFGPs be judged on the efficacy of their opposition to neoliberalism. Indeed, their value and vitality reside in the everyday activities of cultivating and sharing food and enjoying the social relations that emerge from this. However, the general desire to reverse environmental and ecological degradation, and improve social relations, through collective solidarity are ubiquitously present in GCFGPs, yet few projects seem to strongly articulate how political and economic power relations confound the realization of radical transformation on a meaningful scale. This is likely, in no small part, to be attributable to the deliberate obfuscation of the neoliberal project through its pan-political strategy alongside decades of normalization through state policies, media, and undemocratic work conditions.

It is notable that the two movements identified with strong counter-neoliberal ethics, permaculture and slow food, arose in the early phases of neoliberalism’s rise to dominance. These movements also express their values in a positive regenerative frame rather than as a negation, which may have contributed to their longevity. The body of literature examining GCFGPs as counter-hegemonic spaces is sparse, particularly in the UK. Further research could examine the themes set out in this review, especially regarding the quality of defined values and ethics, social dynamics, cultural embodiment, and experiences of pleasure and celebration. Crossan et al., 2016) noted a significant positive change in the verve of an interview when they moved from office to garden. This emphasizes the significant interrelationality between people and the physical environment in the creation of place and community.

References

Adams, G., Estrada‐Villalta, S., Sullivan, D. & Markus, H. R., 2019. The psychology of neoliberalism and

the neoliberalism of psychology. Journal of Social Issues, 75(1), pp. 189-216.

Amin, S., 2009. Capitalism and the ecological footprint. Monthly Review, 61(6), pp. 19-30.

Antonio, R. J., 2007. Chapter 3: The Cultural Construction of Neoliberal Globalisation. In: G. Ritzer, ed.

The Blackwell Companion to Globalisation. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 67-83.

Ayers, A. J. & Saad-Filho, A., 2015. Democracy against Neoliberalism: Paradoxes, Limitations,

Transcendence. Critical Sociology, 41(4-5), pp. 597-618.

Birch, K., 2017. A Research Agenda for Neoliberalism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Bonanno, A. & Wolf, S., 2018a. Introduction. In: A. Bonanno & S. Wolf, eds. Resistance to the Neoliberal

Agri-Food Regime: A critical analysis. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 1-18.

Bonanno, A. & Wolf, S., 2018b. The contradictions of resistance to neoliberal agrifood. In: A. Bonanno &

S. Wolf, eds. Resistance to the Neoliberal Agri-Food Regime: A Critical Analysis. Abingdon: Routledge, pp.

210-226.

Boyd, R. & Richerson, P. J., 2009. Culture and the evolution of human cooperation. Philosophical

Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1533), pp. 3281-3288.

Chandler, D. & Reid, J. D. M., 2016. The neoliberal subject: Resilience, adaptation and vulnerability.

London: Rowman & Littlefield International.

Chun, C. W., 2016. Exploring neoliberal Language, discourses and identities. In: S. Preece, ed. The

Routledge Handbook of Language and Identity. London: Routledge, pp. 558-571.

Clayton, S. & Opotow, S., 2003. Introduction: Identity and the natural environment. In: S. Clayton & S.

Opotow, eds. Identity and the natural environment: The psychological significance of nature. London :

MIT Press, pp. 1-24.

Crompton, T. & Kasser, T., 2009. Meeting environmental challenges: The role of human identity,

Godalming: WWF-UK.

Crossan, J., Cumbers, A., McMaster, R. & Shaw, D., 2016. Contesting neoliberal urbanism in Glasgow's

community gardens: The practice of DIY citizenship. Antipode, 48(4), pp. 937-955.

Cumbers, A., Shaw, D., Crossan, J. & McMaster, R., 2018. The work of community gardens: Reclaiming

place for community in the city. Work, employment and society, 32(1), pp. 133-149.

Davies, G., 2019. Revealed: The Thousands of Public Spaces Lost to the Council Funding Crisis. [Online]

Available at: https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2019-03-04/sold-from-under-you

[Accessed 09 05 2019].

Dean, J., 2015. Volunteering, the market, and neoliberalism. People, Place and Policy, 9(2), pp. 139-148.

Dej, E., 2016. Psychocentrism and Homelessness: The Pathologization/Responsibilization Paradox.

Studies in Social Justice, 10(1), pp. 117-135.

Dietz, R. & O'Neill, D., 2013. Enough is enough: Building a sustainable economy in a world of finite

resources. London: Routledge.

Dilts, A., 2011. From ‘entrepreneur of the self’to ‘care of the self’: Neoliberal governmentality and

Foucault’s ethics. Foucault Studies, Volume 12, pp. 130-146.

Dobernig, K. & Stagl, S., 2015. Growing a lifestyle movement? Exploring identity‐work and lifestyle

politics in urban food cultivation. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(5), pp. 452-458.

Elliot, J., 2013. Suffering Agency: Imagining Neoliberal Personhood in North America and Britain. Social

Text 115, 31(2), pp. 83-101.

Epstein, G. A., 2005. Introduction: Financialization and the World Economy. In: G. A. Epstein, ed.

Financialization and the World Economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 3-16.

Fine, B. & Saad-Filho, A., 2017. Thirteen things you need to know about neoliberalism. Critical Sociology,

43(4-5), pp. 685-706.

Flachs, A., 2010. Food for thought: The social impact of community gardens in the greater Cleveland

area. Electronic Green Journal, 1(30).

Gilbert, J., 2014. Common Ground: Democracy and Collectivity in an Age of Individualism. London: Pluto

Press.

Greenhouse, C. J., 2010. Ethnographies of neoliberalism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Grouzet, F. M. et al., 2005. The structure of goal contents across 15 cultures. Journal of personality and

social psychology, 89(5), pp. 800-816.

Hamann, T. H., 2009. Neoliberalism, governmentality, and ethics. Foucault studies, Volume 6, pp. 37-59.

Harvey, D., 2007. Neoliberalism as creative destruction. The annals of the American academy of political

and social science, 610(1), pp. 21-44.

Hein, G. et al., 2010. Neural responses to ingroup and outgroup members' suffering predict individual

differences in costly helping. Neuron, 68(1), pp. 149-160.

Hogg, M. A. & Reid, S. A., 2006. Social identity, self-categorization, and the communication of group

norms. Communication theory, 16(1), pp. 7-30.

Hudson, R., 2009. Life on the Edge: Navigating the Competitive Tensions between the ‘social’ and the

‘economic’ in the Social Economy and in Its Relations to the Mainstream. Journal of Economic

Geography, 9(4), pp. 493-510.

Hughes, B., 2015. Disabled people as counterfeit citizens: The politics of resentment past and present.

Disability & Society, 30(7), pp. 991-1004.

Hughes, B. L., Ambady, N. & Zaki, J., 2017. Trusting outgroup, but not ingroup members, requires

control: neural and behavioral evidence. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 12(3), pp. 372-381.

Ignatow, G., 2007. Theories of embodied knowledge: New directions for cultural and cognitive

sociology?. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 37(2), pp. 115-135.

Ignatow, G., 2015. Embodiment and Culture. In: J. D. Wright, ed. The International Encyclopedia of the

Social and Behavioural Sciences (2nd Ed: Vol 7). Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 415-419.

Ivanova, D. et al., 2016. Environmental impact assessment of household consumption. Journal of

Industrial Ecology, 20(3), pp. 526-536.

Kasser, T., 2016. Materialistic values and goals. Annual review of psychology, Volume 67, pp. 489-514.

Kimbrell, A., 2002. The fatal harvest reader: The tragedy of industrial agriculture. 2nd ed. Washington:

Island Press.

Kis, B., 2014. Community-supported agriculture from the perspective of health and leisure. Annals of

Leisure Research, 17(3), pp. 281-295.

Lawson, N., Davies, G. & Sheffield, H., 2019. Their community spaces are being sold off but these people

are fighting back. [Online]

Available at: https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2019-03-06/communities-fighting-back-

against-council-sell-offs

[Accessed 2019 05 09].

Levine, M., Prosser, A., Evans, D. & Reicher, S., 2005. Identity and emergency intervention: How social

group membership and inclusiveness of group boundaries shape helping behavior. Personality and social

psychology bulletin, 31(4), pp. 443-453.

Lewis, S. L. & Maslin, M. A., 2015. Defining the anthropocene. Nature, Volume 519, pp. 171-180.

Lindenberg, S. & Steg, L., 2014. Goal Framing Theory and Norm-Guided Environmental Behaviour. In: H.

C. M. van Trijp, ed. Encouraging Sustainable Behaviour: Psychology and the Environment. Hove:

Psychology Press, pp. 37-54.

Liu, P., Gilchrist, P., Taylor, B. & Ravenscroft, N., 2017. The spaces and times of community farming.

Agriculture and Human Values, 34(2), pp. 363-375.

Lizardo, O., 2015. Culture, Cognition and Embodiment. In: J. D. Wright, ed. International Encyclopedia of

the Social and Behavioural Sciences (2nd Ed:Vol 7). Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 576-581.

Lumber, R., Richardson, M. & Sheffield, D., 2018. The Seven Pathways to Nature Connectedness: A Focus

Group Exploration. European Journal of Ecopsychology, Volume 6, pp. 47-68.

Mair, H., Sumner, J. & Rotteau, L., 2008. The politics of eating: Food practices as critically reflexive

leisure. Leisure/Loisir, 32(2), pp. 379-405.

McChesney, R. W., 2001. Global media, neoliberalism, and imperialism. Monthly Review-New York,

52(10), pp. 1-19.

McClintock, N., 2014. Radical, reformist, and garden-variety neoliberal: coming to terms with urban

agriculture's contradictions. Local Environment, 19(2), pp. 147-171.

McGuigan, J., 2014. The Neoliberal Self. Culture Unbound: Journal of Current Cultural Research, 6(1), pp.

223-240.

Melucci, A., 1995. The process of collective identity: Social movements, protest and contention. In: H.

Johnston & B. Klandermans, eds. Social Movements and Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Press, pp. 41-63.

Milbourne, P., 2012. Everyday (in) justices and ordinary environmentalisms: community gardening in

disadvantaged urban neighbourhoods. Local Environment, 17(9), pp. 943-957.

Mirowski, P. & Plehwe, D., 2009. The Road from Mont Pèlerin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Moore, J. W., 2017. The Capitalocene, Part I: On the nature and origins of our ecological crisis. The

Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(3), pp. 594-630.

Moore, J. W., 2018. The Capitalocene Part II: accumulation by appropriation and the centrality of unpaid

work/energy. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 45(2), pp. 237-279.

Mountz, A. et al., 2015. For slow scholarship: A feminist politics of resistance through collective action in

the neoliberal university. ACME: an international E-journal for critical geographies, 14(4), pp. 1236-1259.

Murtagh, A., 2010. A quiet revolution? Beneath the surface of Ireland's alternative food initiatives. Irish

Geography, 43(2), pp. 149-159.

Neal, L. & Williamson, J., 2014. Capitalism Volume 1. The rise of Capitalism: From Ancient Origins to

1848. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Paerl, H. W. & Scott, T. J., 2010. Throwing fuel on the fire: synergistic effects of excessive nitrogen inputs

and global warming on harmful algal blooms. Environmental Science and Technology, 44(20), pp. 7756-

7758.

Perkins, J., 2004. Confessions of an Economic Hit Man. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Pickerill, J., 2015. Permaculture in Practice: Low Impact Development in Britain. In: J. Lockyer & J. R.

Veteto, eds. Environmental Anthropology Engaging Ecotopia: Bioregionalism, Permaculture, and

Ecovillages. Oxford: Berghahn Books, pp. 180-194.

Pietrykowski, B., 2004. You are what you eat: The social economy of the slow food movement. Review of

social economy, 62(3), pp. 307-321.

Piketty, T., 2014. Capital in the 21st Century. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Pookulangara, S. & Shephard, A., 2013. Slow fashion movement: Understanding consumer

perceptions—An exploratory study. Journal of retailing and consumer services, 20(2), pp. 200-206.

Pretty, J., 2002. Agri-Culture: Reconnecting People, Land and Nature. London: Earthscan.

Raafat, R. M., Chater, N. & Frith, C., 2009. Herding in humans. Trends in cognitive sciences, 13(10), pp.

420-428.

Ravenscroft, N., Moore, N., Welch, E. & Hanney, R., 2013. Beyond agriculture: The counter-hegemony of

community farming. Agriculture and human values, 30(4), pp. 629-639.

Read, J., 2010. A Genealogoy of Homo-Economicus: Neoliberalism and the Production of Subjectivity. In:

S. Binkley & J. Capetillo-Ponce, eds. A Foucault for the 21st Century: Governmentality, Biopolitics and

Discipline in the New Millennium. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 2-15.

Shin, H. & Park, J. S. Y., 2016. Researching language and neoliberalism. Journal of Multilingual and

Multicultural Development, 37(5), pp. 443-452.

Sierra Caballero, F., 2018. Imperialism and Hegemonic Information in Latin America: The Media Coup in

Venezuela vs. The Criminalization of Protest in Mexico. In: J. Pedro- Carañana, D. Broudy & J. Klaehn,

eds. The Propaganda Model Today: Filtering Perception and Awareness. London: University of

Westminster Press., p. 237–248.

Slobodian, Q., 2018. Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism. 1st ed. Cambridge:

Harvard University Press.

Smith, A. & Stirling, A., 2018. Innovation, sustainability and democracy: an analysis of grassroots

contributions. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 6(1), pp. 64-97.

Smith, P. et al., 2016. Global change pressures on soils from land use and management. Global Change

Biology, 22(3), pp. 1008-1028.

Sonnino, R. & Griggs-Trevarthen, C., 2013. A resilient social economy? Insights from the community food

sector in the UK. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(3-4), pp. 272-292.

Sonti, N. F. & Svendsen, E. S., 2018. Why Garden? Personal and Abiding Motivations for Community

Gardening in New York City. Society & natural resources, 31(10), pp. 1189-1205.

Spilková, J. & Rypáčková, P., 2019. Prague’s community gardening in liquid times: challenges in the

creation of spaces for social connection. Leisure Studies, pp. 1-12.

Steffen, W., Crutzen, P. J. & McNeill, J. R., 2007. The Anthropocene: are humans now overwhelming the

great forces of nature. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 36(8), pp. 614-622.

Sumner, J., Mair, H. & Nelson, E., 2010. Putting the culture back into agriculture: civic engagement,

community and the celebration of local food. International journal of agricultural sustainability, 8(1-2),

pp. 54-61.

Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P. & Flament, C., 1971. Social categorization and intergroup behaviour.

European journal of social psychology, 1(2), pp. 149-178.

Thompson, J., 2012. Incredible Edible–social and environmental entrepreneurship in the era of the “Big

Society”. Social Enterprise Journal, 8(3), pp. 237-250.